Traveling around New Zealand's South Island with Beach's Motorcycle Adventures

I'M GAZING OUT over two miles of deserted beach between headlands at the Tasman Sea at dawn. Behind me semi-tropical vegetation with sweeps of giant ferns and palm trees is backed by abrupt limestone cliffs that soar straight to the sky. Here it is, the end of the trip, and I don't want this to end.

With most of these organized motorcycle tours I'm ready to go home after two weeks; I've had a great time and all that, but enough is enough, let's pack up and get on the plane. Not this time.

Maybe New Zealand is too much like home. I'm on the west coast of the South Island, at a place called Punakaikio, and it is much like California's Big Sur coast, near where I live. Only this is actually a bit better, being lusher and less trafficked -- until I remind myself that this stretch of real estate gets more than 200 inches of rain a year. We have been lucky with the weather.

I've never talked with anyone who has not loved taking a motorcycle trip through New Zealand, but there have been two consistent complaints... it is too far away and too wet. Not much can be dome about that 12-hour-plus flight from California, but in the 15 days Sue and I have been here it has rained only twice - and that was between midnight and six o'clock, as things should be in Camelot.

Touring this distant South Pacific island by bike is not really an adventure, unless you count riding on the left as being adventurous, but it is a very beautiful place, with beautiful roads. Which is really what these organized motorcycle tours are all about, taking you to a new place and cramming a great deal of excellent riding into a couple of weeks.

Twelve days before 28 of us - 26 Yanks, one Brit, one Ozzie-had convened in Christchurch, the major city on the South Island, where we were wined and dined and told by our guides what to expect on the trip: stunning scenery, untrafficked roads, great people and maybe a hit of rain now and then. The first three were spot on, while the fourth, gladly, never came about.

Our route would follow a very squiggly 2,000-mile figure-eight around the island. We rode out of town as a group, 16 bikes plus two guides on bikes, plus the baggage-carrying chase vehicle, but within an hour or two the group had splintered into individuals and pairs traveling at their own chosen speeds. As it should be. With no language problems, and little chance of getting lost, nobody felt any need to follow a guide. Though we would often get together at recommended lunch spots.

Leaving the fertile plains of the east coast, we headed over Burke Pass to the central valleys, where flocks of Romney sheep hold sway and the snow-capped peaks of the Southern Alps were glimpsed on the distant horizon.

Look at your map of the world; the South Island lies roughly 40 to 46 degrees south, which puts it about as far south of the equator as New England or Oregon are to the north. From Cape Farewell in the north to southernmost Bluff is less than 500 kiwiflying (except the kiwi bird cannot fly; ha, ha!) miles, and the island is never more than 150 miles wide, an oblong of some 58,000 square miles in the middle of the ocean.

The terrain is spectacular; think of a slab of central Colorado surrounded by ocean. Mt. Cook, the highest peak in the Alps at over 12,500 feet, is a mere 20 miles from the sea; the inland valleys tend to be dry; while the coasts are almost tropical. And with only a million people on the island, the place ain't crowded.

Hundreds of miles of good two lane asphalt, no traffic lights except in the odd city; and the biggest hazard seems to be herds of cattle or woollies blocking the road as they move from pasture to pasture.

After a night at Twizel, south of Mt. Cook, we returned to the east (Pacific) coast - the Tasman Sea lies to the west. And the little roads the guides could point us to were certainly the frosting on this two-wheeled cake. For sheer riding joy the Ngapara Road (Ocean to Alps Scenic Highway,) to Oamaru provided unparalleled motorcycling bliss, wending and weaving its way through the valleys, over hills, with green fields, small farms - such a ride cannot really be described, it has to be ridden to do it justice.

Dunedin, the Scottish capitol of the southern hemisphere, was our second small urban foray, tucked into the hills at the south end of Otago Harbor, a long bay protected by the Otago Peninsula. The Victorian buildings attract the architectural eye, but the motorcyclist heads toward Baldwin Street, reputed to be the steepest paved road in the world with its 3:1 slope, a 2.86 gradient at its most severe. Ever ride your bike up a roller-coaster?

We were staying the night in pseudo-aristocratic elegance, at Larnach Castle, a few miles out of town on the peninsula, with views of the bay to die, or pay dearly for. The "castle" was built in the 1870s by William Larnach, a banker and politician; unfortunately the gent had rather a dysfunctional family; and ended tip shooting himself after his third wife ran off with his son from his first marrage. There is nothing new on "Oprah."

I could write this whole story on the Larnach experience, but I have to move on. We rode over the west side of the island where the group was broken up and assigned to various hospitable farmhouses for two nights. Delightful. And in between we ran our bikes along the superb road to Milford Sound, the centerpiece of Fiordland National Park, and spent an afternoon aboard the good ship Milford Wanderer, sailing under waterfalls and watching dolphins play.

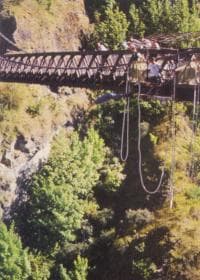

Then it was off to Queenstown, headquarters for New Zealand's "adventure" sports. In and around Q'town you can raise your adrenaline levels in any number of ways, from jet-boating to sky-diving, flying a P-51 Mustang or bungee-jumping.

A fellow named A.J. Hackett set up the first commercial bungee site in 1988, at an abandoned bridge over the Kawarau River, and has become a rich man since then. If you go to Paris, you have to go to the top of the Eiffel Tower; if you go to Q'town, you have to do a bungee jump. Even though it is the most unnatural thing in the world for your neural synapses to cope with, making parachuting look like a romp in the sandbox. The five M.D.s along on the trip all counseled against the jump, saying my back would suffer, my eyeballs would fill with blood, etc. A man's gotta do what a man's gotta do ...been there, done that.

Then it was over the Haas Pass and up the West Coast, which is usually wet, but for us was sunny. Some people helicoptered up to the glaciers in the Alps so that they could throw snowballs at one another, others of us went to the beach. At Greymouth (mouth of the Grey River) we turned and headed east over Lewis Pass and spent the night at Hanmer Springs, where gouts of hot water burst out of the ground. Then along to Kaikoura and up the east coast to Picton, and the Queen Charlotte Drive toward Nelson. Can't beat that stretch of pavement with a stick; gcod road, good riding.

At Nelson, with a free day, I abandoned a temporarily ailing wife and shot north around Abel Tasman National Park and up to Cape Farewell. Tasman was the first European to make comment about the existence of New Zealand, back in 1612, and the Maoris tried to dissuade further exploration by killing four of his sailors. It worked for 200 wars, but the British set up the New Zealand Company and came to land at Nelson in 1841, dropping off a bunch of settlers that would, the investors hoped, make the company rich.

Then we had to finish our very squiggley figure-eight, going over the island divide at Hope Saddle and down to Westport and Paparoa National Park. Which is where I began this little dissertation, sitting on the beach levy at Punakaiki.

Fly-or-die tickets said would have to leave on the morrow. We scaled 3,025 foot Arthur's Pass aand returned to Christchurch, handed in the bikes, bought all the souvenirs and sheep skins we could fit in our bags, had a farewell dinner... and left the next day.

Now, if Boeing could just build faster airplanes....